Throughout the mortal life of Jesus of Nazareth, every step taken and every word spoken lead ultimately to [the] Atonement. The raising of Lazarus sets in motion the last days of Christ’s earthly ministry. For the Christian world, the places and settings wherein Jesus takes His final steps toward the Atonement have become hallowed: the Upper Room, the Garden of Gethsemane, Calvary, and the Empty Tomb.

KENT BROWN: As Lazarus emerges from this tomb, Jesus in effect steps closer to His own, witnessed by both friends and foes. The raising of Lazarus becomes an undeniable sign that this man possesses power over death and life. For His friends, it is a joyous miracle, and the multitude will later sing, “Blessed be the king that cometh in the name of the Lord” (Luke 19:38). But for His enemies, these events, followed by yet another cleansing of the temple, form the final straw. “From that day forth, they took counsel together for to put him to death” (John 11:53).

KERRY MUHLESTEIN: You know, it’s an interesting [thing] that’s happened throughout history, that various groups want to blame others for the crucifixion of the Savior, and various people want to make sure that their group doesn’t get blamed. And as you look at it, certainly there’s the populace that seems to play a role; there’s the Sanhedrin or the rulers of the Jews; the Romans actually put Him to death. It almost seems as if there’s so many people that are brought into play here that it’s clear that no one group can hold the blame here, and that we should be looking for blame.

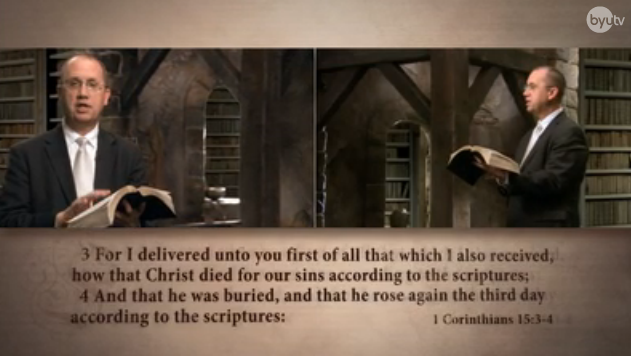

RICHARD HOLZAPFEL: This passage in 1st Corinthians chapter 15, which probably is the earliest account of Jesus’ suffering and death, predating the gospels, predating Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and John, Paul writes this: “For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received.” In other words, I’m not telling you something new; you already know this. I’m telling you a story that already had come to me. So I’m repeating this story that is well known, how that Christ died for our sins according to scripture. And that He was buried, and that He rose again on the third day, according to scripture.

If we’re not careful, we might miss the nuance that Paul’s trying to give us here. He’s trying to give us the historical point: He died, [was] buried, and was raised, but more importantly, it was according to scripture. It had been foreordained. It was known by the prophets and holy and wise men and women who lived during the Old Testament period. They knew the Messiah, the Lord God of Israel, was going to come and do this.

But then one other further nuance, and probably the most significant thing for Paul. Again, notice here it isn’t who’s to blame, it isn’t even like where did it exactly happen, or what day did it happen on. They’re important to the story in the four gospels, but for Paul, it’s that Jesus died, according to the scriptures, for our sins. And that was the real question: why did the Messiah die?

So when we think about Gethsemane, we think about that He took upon Himself the sins of the world, began to suffer there, culminating on the cross. But when I want to talk about the blame game, I think about me. It’s the suffering for human sin, my sins, my transgressions. And as a result, the New Testament really does deal with that issue of why Jesus had to die, not so much who’s to blame.

JOHN S. TANNER: Let’s take a few minutes and kind of orient ourselves. I guess the first thing I’d notice as I look at this view is, there are a lot of hills. And we can see some of these hills, some of the most important ones, right here. In fact let’s begin with the Mount of Olives.

JOHN S. TANNER: Let’s take a few minutes and kind of orient ourselves. I guess the first thing I’d notice as I look at this view is, there are a lot of hills. And we can see some of these hills, some of the most important ones, right here. In fact let’s begin with the Mount of Olives.

KENT BROWN: That of course is the most dominant hill here. And as you come off the slope toward the east, you come down through a little saddle, there’s a rise. We can think of Jesus starting about where that minaret is, down a little bit from that.

JOHN S. TANNER: And that’s the village of Bethany, right.

GAYE STRATHEARN: Yeah, Bethany’s the place, the home of Mary, and Martha, and Lazarus. This is where Jesus stays during that last week of His life. And so He’s going to make the journey every day from Bethany to Jerusalem, but then He comes back to Bethany, probably because John tells us that He loved Mary, Martha, and Lazarus.

JOHN S. TANNER: And as we come further down, we have the Church of All Nations, really down near the bottom of the hill, Mount of Olives. And it’s there where there’s the Garden of Gethsemane. So it crosses the Kidron Brook right there to the Garden of Gethsemane.

Let’s start now, let’s move from the Mount of Olives up to Jerusalem.

KENT BROWN: You start with the walls of the old temple area. There’s actuallya gate that pierces the wall down here closer to the holy mount, called Dung Gate. You come up to Zion’s Gate. Right next to Zion’s Gate, outside the wall is the Dormition Abbey, the building with the great top. And it’s near there, isn’t it, that the Upper Room sits?

GAYE STRATHEARN: Yes. It’s the traditional site where Jesus came and met with His disciples for the Last Supper.

Jesus is very specific in choosing the Passover as the place for His institution of the sacrament. Really what He’s doing there is taking a very, very important celebration in Jewish law, and He’s using that to teach about Himself, and to institutionalize a remembrance of Himself as part of it. The Passover as, as you’ll recall, is a remembrance of the time when Israel was in bondage in Egypt. Moses was there, and he was acting under divine guidance that he was to help the Israelites be released from Egyptian bondage. And so God goes through a series of plagues to try and get Pharaoh to let Israel go. The last of these plagues would be the death of the firstborn—not just the firstborn of people but also of animals. So the Israelites are told that if they will take a lamb, an unblemished lamb, a firstborn lamb, and that they would offer it as a sacrifice, and take the blood of that lamb and put it in the lintel of the door, that when the destroying angel came he would pass over the Israelites and they would not be, be killed.

For 1500 years the Israelites have been gathering together in families and have been looking back, have been retelling that story as the great example of God’s deliverance of His chosen people. So when the Savior chooses the Passover, He’s making a very definite statement to His disciples and all who would listen, right, that He is the Lamb, that He is the representation of that lamb that has been sacrificed for 1500 years.

Now when John the Baptist is going to introduce His disciples to Jesus and kind of get them, you need to follow Him, —he says, “Behold the Lamb of God.” And every Jew would have understood that in terms of the Passover. Christ is the Paschal Lamb. What He would do on the next day, as He was a sinless being, who was the Firstborn of the Father, the Only Begotten Son in the flesh, who would willingly offer Himself as a sacrament for all of those who would come unto Him, He becomes the Paschal Lamb. And so He uses that as the transition from what was happening in the old covenant to what would be understood in the new covenant.

It’s interesting to me that the earliest account of the institution of the sacrament is not found actually in the four gospels, but it’s found in 1st Corinthians chapter 11. Now what had been happening in Corinth, there’d been problems with the sacrament, and so Paul is writing to them, trying to straighten some things out. And I just want to make a couple of notes here.

In verse 23 he says, “For I have received of the Lord that which I have also delivered to you.” Now that word received and delivered [are] technical terms. I am formally handing over to you that which I have formally received. And of course Paul wasn’t there during the events of the Last Supper, but he has learnt about it, should that be from the disciples or maybe even from the Lord Himself. And he goes through and he talks about what happened there, and verse 24: “And when he had given thanks, he brake it and he said, Take eat, this is my body which is broken for you. This do in remembrance of me. And after the same manner also he took the cup when he had supped, saying, This cup is the New Testament in my blood. This do you as oft as you drink it, in remembrance of me.”

Now one of the significant differences about Paul’s account than what we find in the four gospel is the word remembrance, that the partaking of the bread and the wine is in remembrance of what Jesus did. There’s only one place, and that’s in Luke, where He actually uses the word remembrance. Now what’s interesting to me about this, is when we go to the account in 3rd Nephi, where Jesus institutes the sacrament amongst the people in the Americas, it’s very clear, in saying that this is done in remembrance. So the significant thing for me is, the earliest account of the sacrament that we have in the Bible, in 1st Corinthians chapter 11, is actually in many respects closer to the 3rd Nephi account than it is to the gospel accounts. This is one of those places again where I think that the Book of Mormon is helping us to understand and recognize the historical things that are going on in the early Christian church.

JOHN F. HALL: But the Last Supper was not only an occasion for teaching, though it was that. It consisted of an ordinance, a very sacred ordinance, that the Savior performed at least for the apostles—the washing of the feet. And you’ll recall that Peter objected to the Savior washing his feet. The Savior was far too important and loved of Peter to be allowed to wash his feet. And remember the Savior’ response? It was, Peter, if you don’t allow me to do this, you will not have part of me. And Peter then says, Wash my feet, so that I may be part of you.

Well, the ordinance as performed made those who received it Christ’s own. Their connection with Christ was sealed. They would be Christ’s through all eternity. What a tremendous blessing was given. And it’s in the context of that blessing that the Savior then gives the teachings that we find in the 17th chapter of John.

ALAN K. PARRISH: Well, I think the intercessory prayer, more than anything to me, is Jesus praying earnestly to His Father that somehow those that He’s leaving behind, these great men and women, disciples of Jesus, would somehow have enough comfort and reassurance, protection and help, that they might in their service, their ministries, approach the oneness that the Father has. And I think the most urgent and touching part of the prayer is the appeal, that they may be one as we are one, or like we are one. That oneness is the center I think of what He is praying about. Knowing no doubt the hardships that all of them would face. He had just referred to Peter, before the cock would crow on that great night, tragic night, he would deny Christ, or his acquaintance with Christ, association with Christ, three times. So Jesus knew the trials they would have. And yet His earnest prayer, perhaps that’s the main reason for it, that they would have the comfort, plus the oneness that would enable them to do what they needed to do in—as His apostles.

GAYE STRATHEARN: The events that begin here in Gethsemane are viewed very differently by Latter-day Saints than by much of Christianity today. For many Christians, Gethsemane is the place where Jesus prepared both spiritually and psychologically for His coming crucifixion. For Latter-day Saints, however, Gethsemane is the focal point for the Atonement, the place where the sins of the world crushed down upon Him who was without sin.

CECILIA M. PEEK: The process of preparing oil from olives is a fascinating one. They harvest the olives, and put them first into a massive stone basin, and roll over it a huge wheeled stone that is a crusher, and create from the olives something that is called mash. And already at that stage, when the olives are crushed into this mash, they are crushed beyond recognition. And the process is not completed yet. It’s at this point that they load that mash into wicker baskets and stack them, and then the olive press finally comes into play, where they press down on those, and out of that mash slowly they, they eke out, and there oozes out of the wicker baskets the first water and oil that comes out of the olives. And in fact the first fluid that flows out is red like blood, and stains what it lands on. So the image of Christ’s suffering in a site that is called the olive press describes in fact His suffering and His bleeding.