JOHN W. WELCH: To understand what’s going on in the trial of Jesus, I think we have to appreciate that they were in an emergency mode. They felt that a crisis was about to happen. And not just a crisis of some kind of riot, or rebellion, or that the Romans were going to get upset and maybe take the temple away. Here was Jesus, who had power to still the storm. Here was Jesus who had just raised Lazarus from the dead, which was the tipping point in finally pushing the chief priests over the line in saying, we must now take action against Jesus.

These people are scared. They’re afraid that Jesus, if He’s not the Son of God, must be using the powers of evil forces to work the miracles that He is working. And one of the requirements for being a member of the Sanhedrin was the ability to differentiate between what they called white magic and black magic. Good miracles, good signs, which were things that Moses himself had done, which obviously were legitimate. But then there were black magic acts, and things that should not happen.

I was reading in King Benjamin’s speech in Mosiah chapter 3. And interestingly, in the words of the angel, prophesying to Benjamin about the coming of Jesus Christ, he says that He would go forth “working mighty miracles, such as healing the sick, raising the dead, causing the lame to walk, the blind to receive their sight and the deaf to hear, and curing all manner of diseases” (Mosiah 3:5). We think that’s a good thing. But the reaction that was prophesied was that even though He shall do these things, “even after all this they shall consider him a man and say that he hath a devil,” that He’s doing these things by the power of Satan. “And therefore they shall scourge him, and crucify him” (Mosiah 3:9).

JOHN F. HALL: When He was produced by the Sanhedrin before Pilate, John says He had been proven to be—so presumably proven in the court of the Sanhedrin—a malefactor. Now malefactor is an English word that just means a general wrongdoer. But it comes from a Latin word, malefikium, which is a specific crime, a specific legal charge, namely a charge of practicing magic. And if we look at the text of John’s gospel, the word that’s found there is kakopoios. Kakopoios is the Greek word for malefikus, which is translated “malefactor,” but means in fact someone practicing magic.

JOHN F. HALL: When He was produced by the Sanhedrin before Pilate, John says He had been proven to be—so presumably proven in the court of the Sanhedrin—a malefactor. Now malefactor is an English word that just means a general wrongdoer. But it comes from a Latin word, malefikium, which is a specific crime, a specific legal charge, namely a charge of practicing magic. And if we look at the text of John’s gospel, the word that’s found there is kakopoios. Kakopoios is the Greek word for malefikus, which is translated “malefactor,” but means in fact someone practicing magic.

JOHN W. WELCH: At that point, Pilate entered into the judgment hall again and called Jesus to Him and said, All right, let’s raise the final accusation. Are you the King of the Jews? This phrase, King of the Jews, was a title that had been given by Augustus Caesar to Herod. And so it was a politically charged term. Jesus doesn’t ever say, Yes, I am the King of the Jews, He just says, I’m a king, but my kingdom is not of this world. And Pilate seems to be quite satisfied with that.

At that point, Jesus answered and said, “Thou sayest that I am a king. To this end was I born, and for this cause came I into the world, that I should bear witness unto the truth. Every one that is of the truth heareth my voice” (John 18:37).

At this point, Pilate, who is hoping to find some witness, some truth, to know how to judge this case, says, Well, “what is truth?” This is a difficult case. And he decides that finds no basis for an accusation against Jesus, goes back out to the Jews, and says, “I find in him no fault.” And the Greek word here is, no legal cause of action, against Him.

JOHN F. HALL: And he follows up that statement by doing something that had extreme significance in Roman law. He washed his hands. The washing of the hands we often take as a sign of declaring Christ’s innocence. In Roman law it was a simple procedure by which a presiding magistrate would say that the case before him was not in his jurisdiction.

JOHN W. WELCH: It’s the chief priests, a very small group of very powerful Sadducees, who are the constant players moving this along. It is not the Jews as a people. In fact most of the Jews in Jerusalem welcomed Jesus, accepted Him. It was only a few days before at Palm Sunday that they welcomed Him as their Messiah, shouting, Hosanna, “save us now.” So it’s not the Jews who are killing Jesus. It’s just a few who are pushing this through. And as Peter will say, ignorantly so.

ERIC D. HUNTSMAN: When Caiaphas had been interrogating Jesus, he had asked Him directly, Art thou the Son of the Blessed? (Mark 14:61)—a way of asking if He was the Messiah. And Jesus has said, Thou sayest. Perhaps one of the reasons the Jewish authorities were anxious to see the Romans execute Jesus was not just to pass the buck, but because it would better accomplish their purpose of proving that Jesus was not who He claimed to be, that He was not the Son of the Blessed.

A passage in Deuteronomy said, Cursed is any man who’s hanged on a tree (Deuteronomy 21:23). Stoning would not have shown that Jesus was cursed, but if He were crucified, hung on a cross, they could claim to everyone that He was in fact rejected by God.

Now we are free.

GAYE STRATHEARN: Crucifixion has a long history. It was used by many civilizations in the ancient world. We know of the Assyrians under Shalmaneser III. We have examples in relief of him doing crucifixions. In that instance, it was impaling of people alive, and that was the form of crucifixion. We know that Jews at some point used it against other Jews. But it’s probably the Romans who perfected this and made it an art form of putting people to death.

Crucifixion was chosen because it was a long, slow, painful, horrific death. The Romans could easily have put people to death in a much cheaper way of doing it: beheading them, doing other things. But they chose crucifixion particularly for those who were seen as traitors, thieves, and things like that. It was also meant to be a very, very public form of death. Besides the fact that they’d be left for however long it took for them to die in public areas, that they would have to carry their cross. Now that might mean the cross itself, but it probably means the crossbeam that they would have to carry.

Before they were crucified, the Romans would scourge people, which means that they would whip them with little pieces of bones in the whips. And the idea of this was that they would have open flesh wounds all over their backs and their sides, so that even when they’re up on the cross, they’re feeling that kind of pain, as well as the pain that is associated with the crucifixion.

Now we know that from lots of literary sources about crucifixion, but the reality is, archaeologically we’ve only found one individual that we know was crucified. And that comes in 1968 in a place north of Jerusalem. They found some bones of a person, where the actual nail was still in the bone. And it goes through the calcaneus, which is the heel bone, and that is nailed to the cross. And the way that the nail was here, would indicate that we have the vertical beam, and probably the feet are placed either side of that and then the nail was put through the largest bone that we have in the foot to give it support. Now, something happened with this and the nail bent, so when they took the person down off the cross, they couldn’t get the nail out. And so the nail is still in the bone, and that’s how we know that they were crucified.

PAUL Y. HOSKISSON: All of these things about crucifixion are in the back of the minds of the writers of the New Testament when they’re talking about Christ’s crucifixion. But the symbolism here I think is really important. When we look at 3rd Nephi, chapter 27 verse 14, it brings out the symbolism of the cross here: “And my Father sent me that I might be lifted up upon the cross; and after that I had been lifted up on the cross, that I might draw all men unto me, that as I have been lifted up by men even so should men be lifted up by the Father, to stand before me.”

The symbolism of the cross of being lifted up is a symbol of us being lifted up to eternal life. And we don’t always talk about that aspect of the symbolism of the cross. We tend to concentrate more on the ugly details and the despicable nature of the cross.

I want to say something else too about crucifixion. We know from reading a passage in Josephus that you could survive crucifixion. Josephus talks about his three friends that he saw crucified. And he goes to the Roman general and asks, Can I take them down? The Roman general says, Well of course, take them down. And in spite of the best of care, Josephus says, two of them died. But one survived. Crucifixion is not immediately fatal.

And I think that’s a key element of what’s going on here. Because nobody really killed Christ, as Abinadi explains in Mosiah chapter 15. Christ can’t be killed. He’s part the Father. But He can die. And therefore He chooses to die; He’s not executed. But the execution, or His choice of death, has to be in some manner that people who are not believers, looking on it, will say, Oh He’s been executed, He’s done, that’s over with now. But the believers who are looking on at this will say, as the Roman centurion did, This is the Son of God. He dies of His own free will. He offers Himself on the cross. He’s not killed on the cross.

To me, it brings it full circle back to Adam. Because Adam in his agency freely chose spiritual death to be able to create mortal life. Jesus freely chooses of His own accord mortal death to create spiritual life. So even though the crucifixion is rather ugly and has a long history, it ends up being a very beautiful symbol, and the way that Christ can show that He’s offering Himself freely for us.

JOHN S. TANNER: Outside the city walls of Jerusalem, there stands the place of Roman execution called Golgotha. It was deliberately situated near a busy thoroughfare, just like today, so as to provide a grim reminder to any who passed by what would befall them if they dared oppose Roman authority.

On that Friday morning 2000 years ago, Jesus is nailed to a cross and placed between two common thieves. With most of the apostles in hiding, it was left almost exclusively to the women to witness what would happen to Jesus in the final hours of His mortality. And what they hear and see, even down to the smallest excruciating detail, is a fulfillment of prophecy.

GAYE STRATHEARN: The gospel accounts are going to make some specific references that the things that happen in association with the crucifixion are specifically to the fulfilling of scripture.

Now Matthew is going to do that in terms of the parting of the garments and the casting lots of the garments as a fulfillment of scripture. Now that’s something we would expect from Matthew. Because Matthew throughout his gospel goes out of his way every time Jesus does something significant to say, Thus is it fulfilled in scripture, or thus it is to fulfill something that a certain prophet as said. And we would understand that because his audience is a Jewish audience, and to help them see the connection between Christ of the New Testament and the Messiah of the Old Testament.

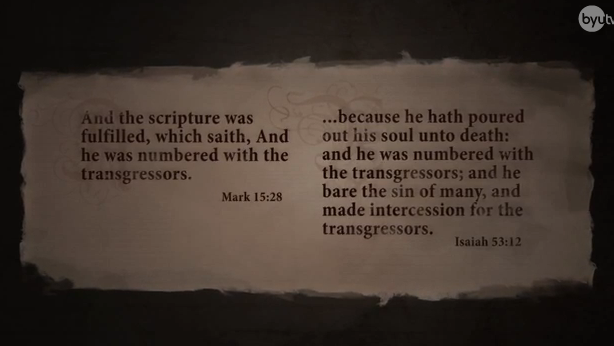

But what’s interesting to me though, is that we’re going to have Mark and John in going to do similar type of things. Mark is going to make reference that, the fact that Jesus is crucified among thieves is a fulfillment of prophecy. Now what’s interesting to me about that is, Mark is writing probably to a Roman audience, an audience that would not be familiar with the Hebrew Bible and the prophecies and things like that, but Mark still makes the point that he wants to show that this is the fulfillment of prophecy.

Likewise, John is going to do the same thing when he talks about Jesus, that He’s on the cross says, “I thirst,” right?. And John again specifically makes mention that this is the fulfillment of prophecy. Now John’s audience may or may not have been aware of the messianic prophecies, but we still have these situations, that they want to make it very, very clear that this isn’t new, this isn’t unexpected. This is the fulfillment of prophecy.

JOSEPH FIELDING MCCONKIE: And so now as this great work and labor is done, He commends His whole ministry into the hands of His Father. And the final expression that Jesus Christ makes on the cross is, “It is finished.” And Joseph Smith, in the Joseph Smith Translation—and we have this in our footnote for Matthew chapter 27, has that readsaying, “Father, it is finished, thy will is done.” And then he yieldeth up the ghost.”

And so what it does is tie the story together from beginning to end. That’s where in a very real sense His Messiahship begins, when He stands and says to the Father in that pre-earth council, I will go and do thy will. I have now completed that assignment, I have accomplished thy will. And so it just is, it just binds and ties the whole plan of salvation together, this whole system of “whom shall I send,” and “I have now completed that work and labor.”

CAMILLE FRONK: With sundown just a short time away, and a concern therefore for having the body of Jesus buried before the commencement of a Sabbath, a man by the name of Joseph of Arimathea, a small town outside of Jerusalem, pleaded with Pilate to care for the body. It appears that Joseph was a councillor, perhaps even a member of the council, the Sanhedrin. And there to accompany him is Nicodemus, another member of that council—ones that most likely were not part of any trial the night before.

Joseph had a tomb for a wealthy man, and he and Nicodemus were there just a short period of time it appears, to wrap the body in the grave clothes, and put what little ointment could be applied. Typically, that was what the women would have done. And there is evidence that there were women from Galilee who were watching there at the cross, and followed Nicodemus and Joseph to the tomb to see where the body was lain.

Apparently there wasn’t time for the typical ritual of preparing the body for burial. And these women couldn’t come back the next day because it was the Sabbath. If that next day was the Passover Sabbath, it’d be then the next day is the weekly Sabbath, it would be another couple of days before they could arrive to the tomb. And the first thing on Sunday morning, they come to the tomb to see if they could, then it appears, anoint the body in the way they would have wanted to previously. We don’t know much about those women of Galilee. We know a name of Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of Joseph and James. These women came back on Sunday morning with all these—this ointment, to make that body smell as sweet as long as possible. And found the tomb was empty.

JOHN S. TANNER: I think sometimes both students and tourists have thought, you have to come to the Holy Land or come to Jerusalem in order to really have an appreciation for the New Testament and for the Savior. But of course that’s got to be untrue. This—He’s the Savior of all time, all the world of the poor who will never have a chance to be here. But in the most important way, every person can come to the Savior, can come to Jesus, by coming there with heart and faith, by scripture study and by prayer. He Himself said, “I stand at the door, and knock; if any man . . . open the door, I will come in and sup with him” (Revelation 3:20). And so that’s a great promise, it’s a great promise to all believers, that you don’t have to be there at the Last Supper, you don’t have to be there in the events of His ministry, or come here to the Holy City. You could actually have Him come into your heart, into your life.

Christ’s final week in mortality is marked by His teachings at the Last Supper, His suffering in Gethsemane, a hearing at Caiaphas’s palace and a trial before Pontius Pilate, and, finally, crucifixion at Golgotha. Here He utters His last words in mortality. “It is finished. Father, into Thy hands I commend my spirit” (John 19:30). These events stand at the pinnacle of His mortal ministry, and lead to His ultimate triumph over physical and spiritual death in the resurrection.